Category Archives: Moscow

Moscow City Streets

Russian long supported trade routes between the Orient and Europe. Moscow was founded as a trade post in the 12th century.

Moscow is the capital city and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural and scientific center in Russia and in Europe. According to Forbes 2011, Moscow has the largest community of billionaires in the world.[14] Moscow is the northernmost megacity on Earth, the most populous city in Europe,[15][16][17] and the 5th largest city proper in the world. It’s also the largest city in Russia with a population of 13 million.

Moscow

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Russian Academy of Sciences; Moscow, Russia

The Russian Academy of Sciences has a tower with a rooftop restaurant with the most beautiful views of Moscow….

The Institute of Europe of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IE RAS) is the authoritative and influential think tank in Russia. Founded in 1987 with the aim of providing scientific understanding and explanation of the dramatic changes in Europe and their prospects, the Institute works on economic, political, social and security issues, established or emerging across Europe.

Institute of Europe RAS

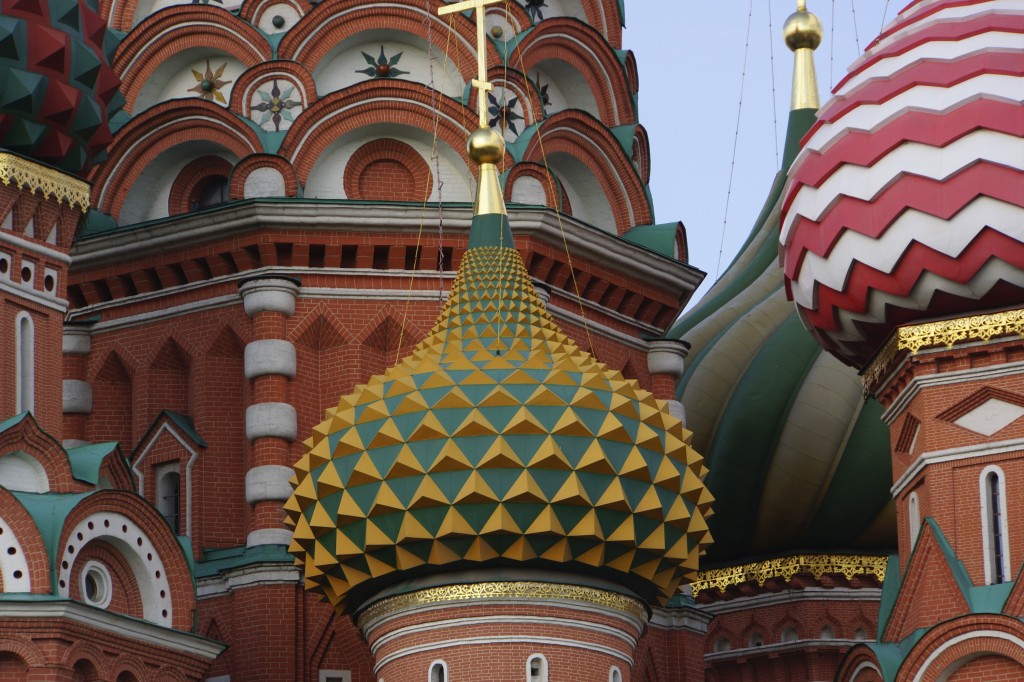

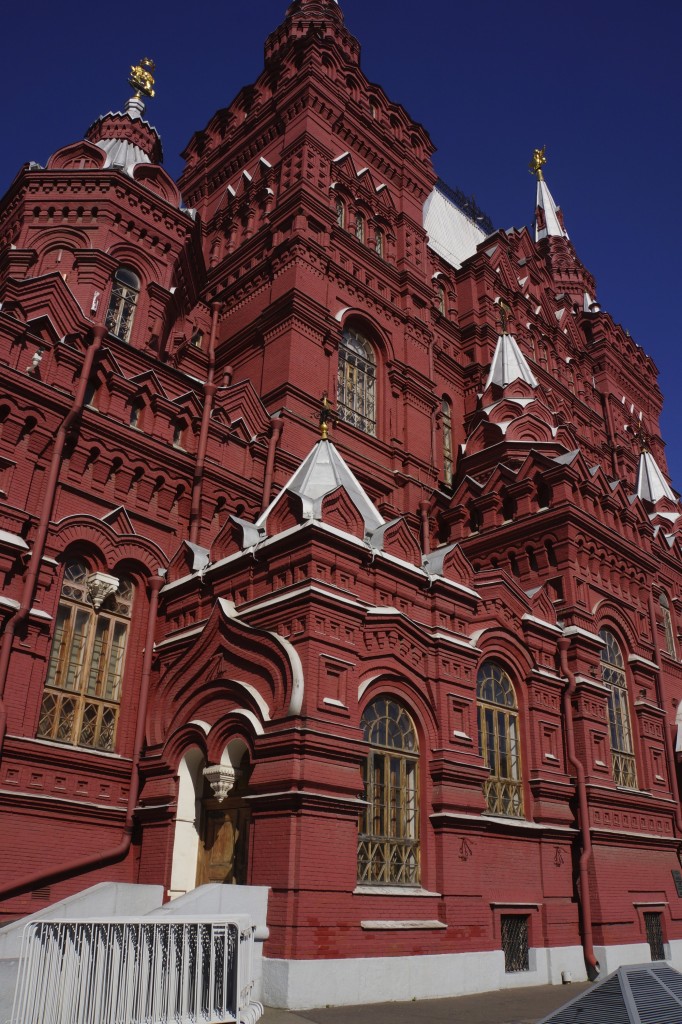

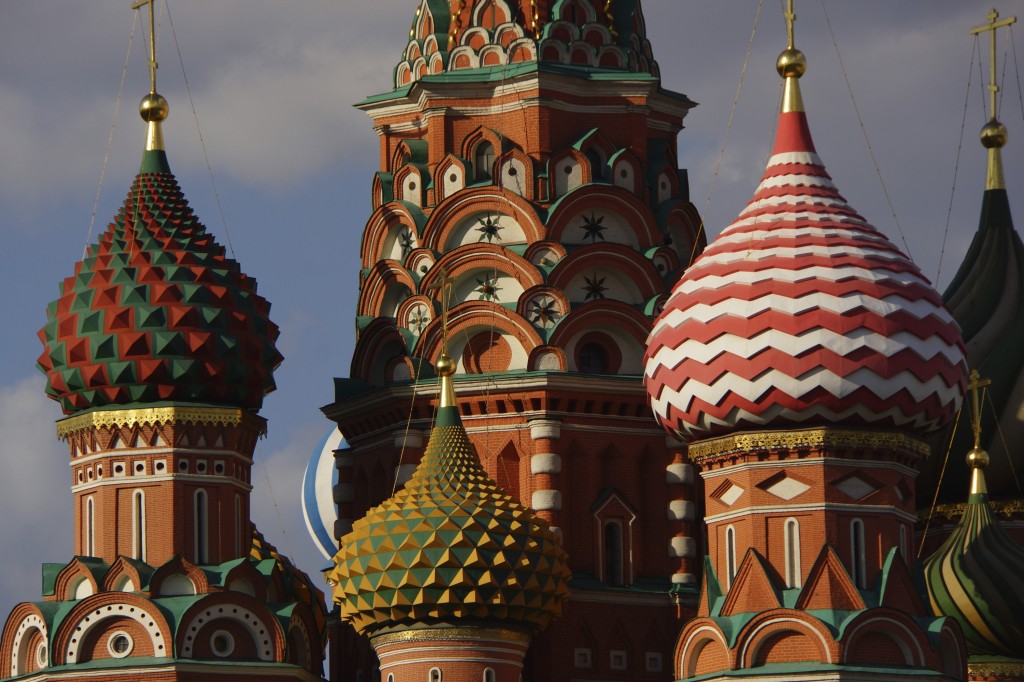

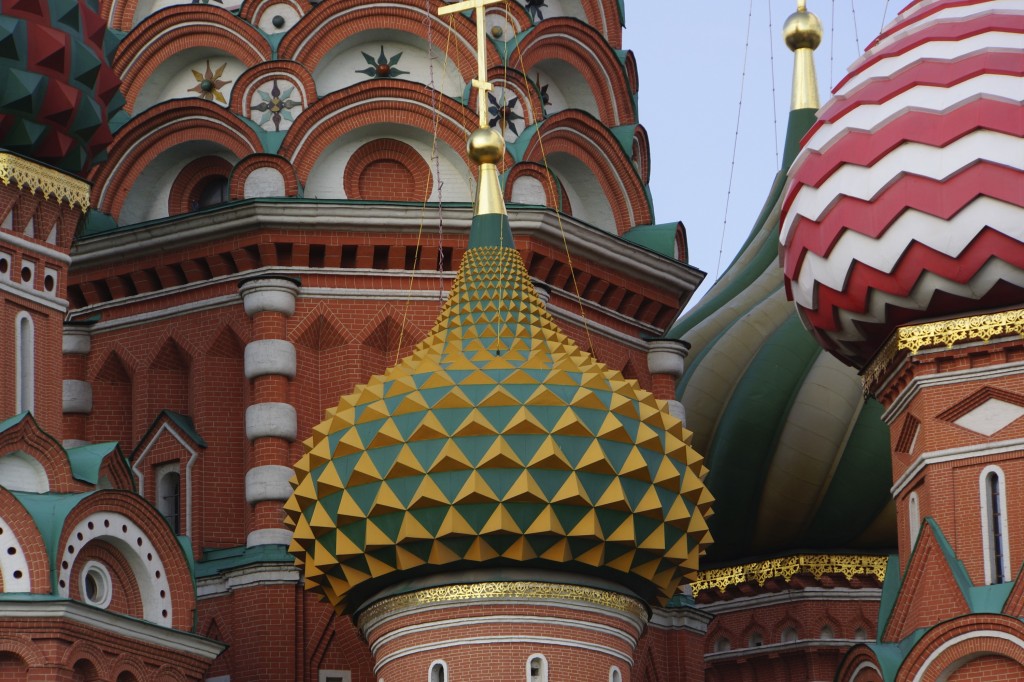

Red Square

The Red Square (Russian: Красная площадь, tr. Krásnaja Plóščaď; IPA: [ˈkrasnəjə ˈploɕːətʲ]) is a city square in Moscow, Russia. The square separates the Kremlin, the former royal citadel and currently the official residence of the President of Russia, from a historic merchant quarter known as Kitai-gorod. The Red Square is often considered the central square of Moscow and all of Russia, because Moscow’s major streets—which connect to Russia’s major highways—originate from the square.

The name Red Square comes neither from the colour of the bricks around it (which, in fact, were whitewashed at certain times in history) nor from the link between the colour red and communism. Rather, the name came about because the Russian word красная (krasnaya) can mean either “red” or “beautiful” (the latter being rather archaic; cf. прекрасная, prekrasnaya).

Red Square

Moscow..The Kremlin

At the center of Moscow is The Kremlin, a village unto itself, with cathedrals, palaces, an enormous concert and congress hall, and of course the seat of presidential power — all surrounded by imposing red-brick walls that extend for 2.5km (1 1/2 miles). On its east side is Red Square, the epicenter of the city and the country. The square abuts a small neighborhood called Kitai-Gorod. This is almost like an annex to the Kremlin, with a dense collection of churches, old merchants’ courtyards, and administrative buildings clustered on quiet streets overlooking the Moscow River. Its name today translates as “Chinatown,” but more likely comes from an old Russian term for battlements because of its proximity to the Kremlin. The area boasts many restaurants but few hotels.

From: travel.nytimes.com/…/moscow/frm_moscow_2448020048.h

Tsar Bell

The history of Russian bell founding goes back to the 10th century, but in the medieval Russian Orthodox Church, bells were not typically rung to indicate church service, but to announce important ceremonies, celebrations, and as an alarm in case of fire or enemy attack. One of the largest of the early bells was the original Tsar Bell, cast in the 15th century. Completed in 1599, it weighed 18,000 kg and required 24 men to ring its clapper. Housed in the original wooden Ivan the Great Bell Tower in the Moscow Kremlin, it crashed to the ground in a fire in the mid-17th century and was broken to pieces.

The second Tsar Bell was cast in 1655, using the remnants of the former bell, but on a much larger scale. This bell weighed 100,000 kg, but was again destroyed by fire in 1701.

After becoming Empress, Anna ordered that the pieces be cast into a new bell with its weight increased by another hundred tons, and dispatched the son of Field Marshal Münnich to solicit technical help from the master craftsmen there. However, a bell of such size was unprecedented, and Münnich was not taken seriously. In 1733, the job was assigned to local foundry masters, Ivan Motorin and his son Mikhail, based on their experience in casting a bronzecannon.

A 10-meter deep pit was dug (near the location of the present bell), with a clay form, and walls reinforced with rammed earth to withstand the pressure of the molten metal. Obtaining the necessary metals proved a challenge, for in addition to the parts of the old bell, an additional 525 kilograms of silver and 72 kilograms of gold were added to the mixture. After months of preparation, casting work commenced at the end of November 1734. The first attempt was not successful, and the project was incomplete when Ivan Motorin died in August, 1735. His son Mikhail carried on the work, and the second attempt at casting succeeded on November 25, 1735. Ornaments were added as the bell was cooling while raised above the casting pit through 1737.

However, before the last ornamentation was completed, a major fire broke out at the Kremlin in May 1737. The fire spread to the temporary wooden support structure for the bell, and fearing damage, guards threw cold water on it, causing eleven cracks, and a huge (11.5 tons) slab to crack off. The fire burned through the wooden supports, and the damaged bell fell back into its casting pit. The Tsar Bell remained in its pit for over a century. Unsuccessful attempts to raise it were made in 1792 and 1819. Napoleon Bonaparte, during his occupation of Moscow in 1812, considered removing it as a trophy to France, but was unable to do so, due to its size and weight.

It was finally successfully raised in the summer of 1836 by the French architect Auguste de Montferrand and placed on a stone pedestal. The broken slab alone is nearly three times larger than the world’s largest bell hung for full circle ringing, the tenor bell at Liverpool Cathedral.

For a time, the bell served as a chapel, with the broken area forming the door

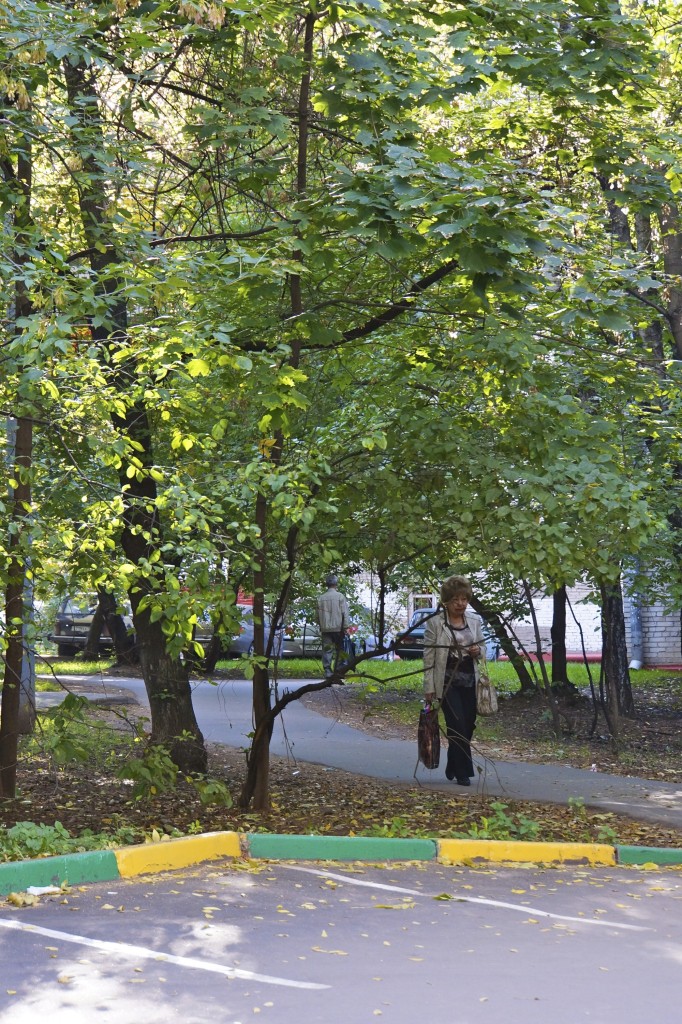

Moscow’s Neighborhoods

Moscow is the largest city in Russia and Europe. The capital of Russia has a population of 13 million. According to Forbes 2011, Moscow has the largest community of billionaires in the world.

Single family homes do not exist in Moscow or St. Petersburg. Everyone lives in apartments. The majority of the population live in mid level, yellow brick apartment buildings in complexes lined up as far as the eye can see. Until Khrushchev’s massive construction project, known as Khruschev’s Thaw, 2 families would share one apartment. Each family would have a bedroom or two and share a common kitchen and bathroom. Kruschev’s Thaw provided enough space for individual families to have their own apartment.

Staying in Moscow is cost prohibitive. Traveler’s stay in hotels embedded in these neighborhoods and take the metro to and from downtown.

The Arbat; Moscow, Russia

A chaotic mass of kiosks, traffic and underpasses, Arbat Square is the link between the vividly contrasting areas of old and new. Expect to come across an impromptu rock concert, kittens and puppies for sale and, in late summer, children selling bulbous hand picked mushrooms (though buying these may not be advisable).

Moscow – Eyewitness Travel

Bosco Cafe; Moscow, Russia

Sip a cappuccino in view of the Kremlin. Munch on lunch while the crowds line up at Lenin’s Mausoleum. Enjoy an afternoon aperitif while admiring St Basil’s domes. This café on the 1st floor of GUM is the only place to sit right on Red Square and marvel at its magnificence.

Lonely Planet review for Bosco Cafe

Moscow’s Metro

The early metro lines were laid very deep underground to be used as bomb shelters during the war. In November 1941, when German troops were looming and the Soviet Union was fighting for survival, Stalin addressed his forces in the central station.

From Eyewitness Travel Moscow.

The Moscow Metro was one of the USSR’s most extravagant architectural projects. Stalin ordered the metro’s artists and architects to design a structure that embodied svet (radiance or brilliance) and svetloe budushchee (a radiant future).[11] With their reflective marble walls, high ceilings and grandiose chandeliers, many Moscow Metro stations have been likened to an “artificial underground sun”.[12] This underground communist paradise[12] reminded its riders that Stalin and his party had delivered something substantial to the people in return for their sacrifices. Most importantly, proletarian labor produced this svetloe budushchee.

The metro design’s emphasis on verticality was a reinforcement of Stalin’s deification[citation needed]. He directed his architects to design structures which would encourage citizens to look up, admiring the station’s art (as if they were looking up to admire the sun and—by extension—him as a god.[13] Another aspect of the apotheosis propaganda was the metro’s electrification; the Moscow Metro’s chandeliers are one of the most beautiful and technologically advanced aspects of the project.

The Moscow Metro is a state-owned enterprise.[2] Its total length is 308.7 km (191.8 mi) and consists of 12 lines and 186 stations. The average daily passenger traffic is 6.6 million. Ridership is highest on weekdays (when the Metro carries over 7 million passengers per day) and lower on weekends. Each line is identified according to an alphanumeric index (usually consisting of a number), a name and a colour. Voice announcements refer to the lines by name. A male voice announces the next station when traveling towards the centre of the city, and a female voice when going away from it. On the circle line the clockwise direction has a male announcer for the stations, while the counter-clockwise direction has a female announcer. The lines are also assigned specific colours for maps and signs. Naming by colour is frequent in colloquial usage, except for the very similar shades of green assigned to the Kakhovskaya Line (route 11), the Zamoskvoretskaya Line (route 2), the Lyublinsko-Dmitrovskaya Line (route 10) and the Butovskaya Line (route L1).

The system operates in an enhanced spoke-hub distribution paradigm, with the majority of rail lines running radially from the centre of Moscow to the outlying areas. The Koltsevaya Line (route 5) forms a 20-kilometre (12 mi)long ring which enables passenger travel between these spokes. Signs showing the stations that can be reached in a given direction are in each station.[3] A complete map is also on each station both inside and outside, and in the trains, but not on the platforms. Most of the stations and lines are underground, but some lines have at-grade and elevated sections. TheFilyovskaya Line is notable for being the only line with most of its route at grade.

From:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moscow_Metro

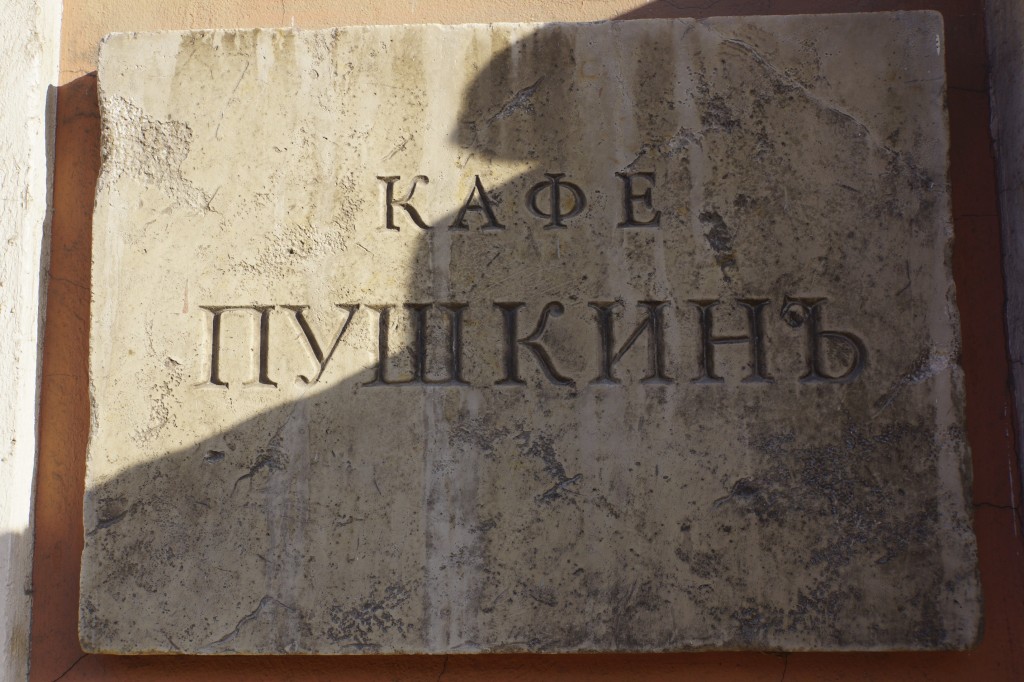

Cafe Pushkin

More than 40 years ago Gilbert Becaud, famous French chansonier, gave performances in Moscow. Returned to France, he wrote a song “Natalie” and dedicated it to Natalie, his Russian interpreter. There are such words in this song: “We are walking around Moscow, visiting the Red Square and you are saying learned words about Lenin, the revolution, but I am thinking: “I wish we sat in the “Café Pushkin”, with snow falling outside the windows, we would be drinking hot chocolate and talking of another things… ”.

The song became incredibly popular in France, and it is no wonder that in Moscow the Frenchmen searched for the “Café Pushkin” and failed to find it because it was solely the poetic fantasy of Becaud. It was the song that compelled Andrey Dellos to create “Café Pushkin”.

And finally on June 4th, 1999, on Tverskoy boulevard Moscow, “Café Pushkin” was opened in a Baroque mansion, which opening was attended by Gilbert Becaud and there he sang his world-famous song “Natalie”.

http://www.cafe-pushkin.ru/en/

The café, which is really a five-star restaurant, is open 24 hours a day and is a local signature. It was a most intriguing place for us. The waiters stood guard around me with my camera. “No pictures! We do not compromise the identity of our patrons.” We lingered over a long lunch next to a table of dark suited, expressionless, silent men in waiting with double parked Mercedes along the curb outside, all in a dark suit with an ear phone at the ready, Right out of a James Bond movie.